Retinal Detachment Surgery

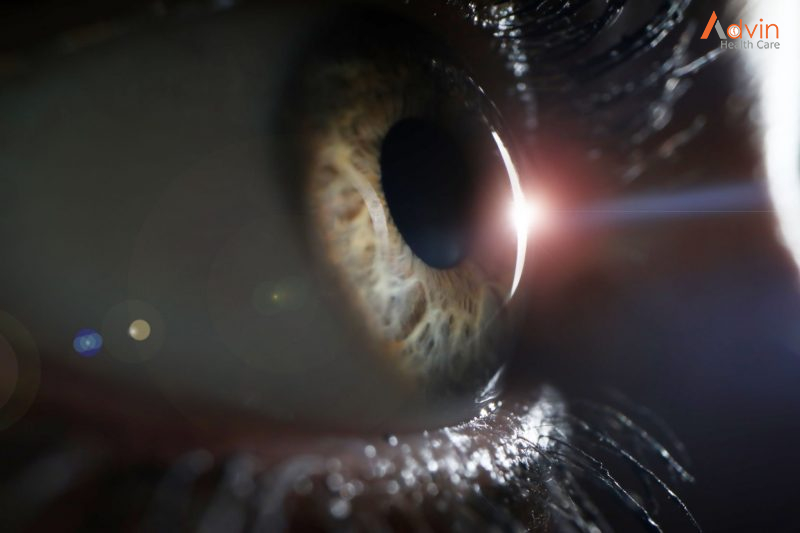

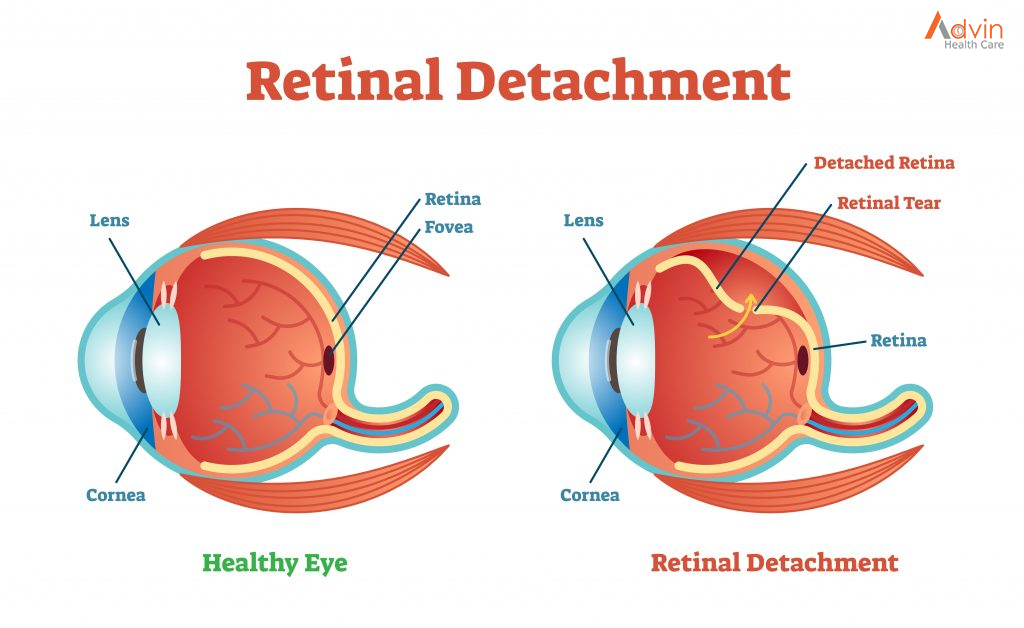

Retinal detachment describes an emergency situation in which a thin layer of tissue (the retina) at the back of the eye pulls away from its normal position.

Retinal detachment separates the retinal cells from the layer of blood vessels that provides oxygen and nourishment to the eye. The longer retinal detachment goes untreated, the greater your risk of permanent vision loss in the affected eye.

Warning signs of retinal detachment may include one or all of the following: reduced vision and the sudden appearance of floaters and flashes of light. Contacting an eye specialist (ophthalmologist) right away can help save your vision.

What is a Retinal Detachment?

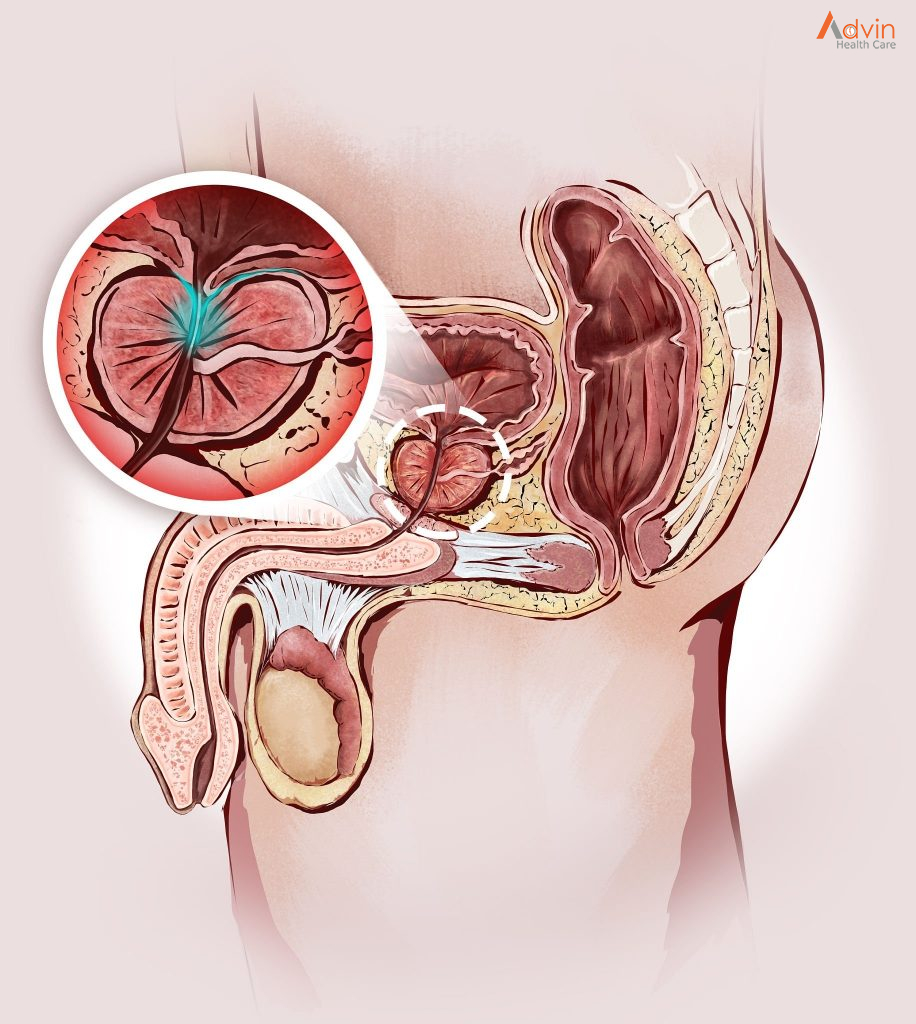

The retina is the light-sensitive layer of nerve tissue that lines the inside of the eye and sends visual messages through the optic nerve to the brain. A retinal detachment occurs when the retina becomes separated from the rest of the layers of the eye. This usually occurs after you develop a tear in the retina. The extent of permanent damage depends on how much of the retina becomes detached and whether or not the centre of the retina (the macula) becomes detached. The macula is made up of special nerve cells that provide the sharp central vision needed for seeing fine detail. If your macula has become detached, you have a poorer visual prognosis and you may not regain good enough vision to read or drive with that eye even after successful surgery.

Why do I have a Retinal Detachment? What are the symptoms?

A retinal detachment occurs when a tear forms in the retina allowing fluid to get under the retina forming a detachment. They are more common in patients who are very near- sighted, have a family history of retinal detachment, and in eyes that have had prior trauma or eye surgery. Patients often complain of flashes, new floaters and a shadow forming in their vision when a retinal detachment occurs.

Surgical Procedure

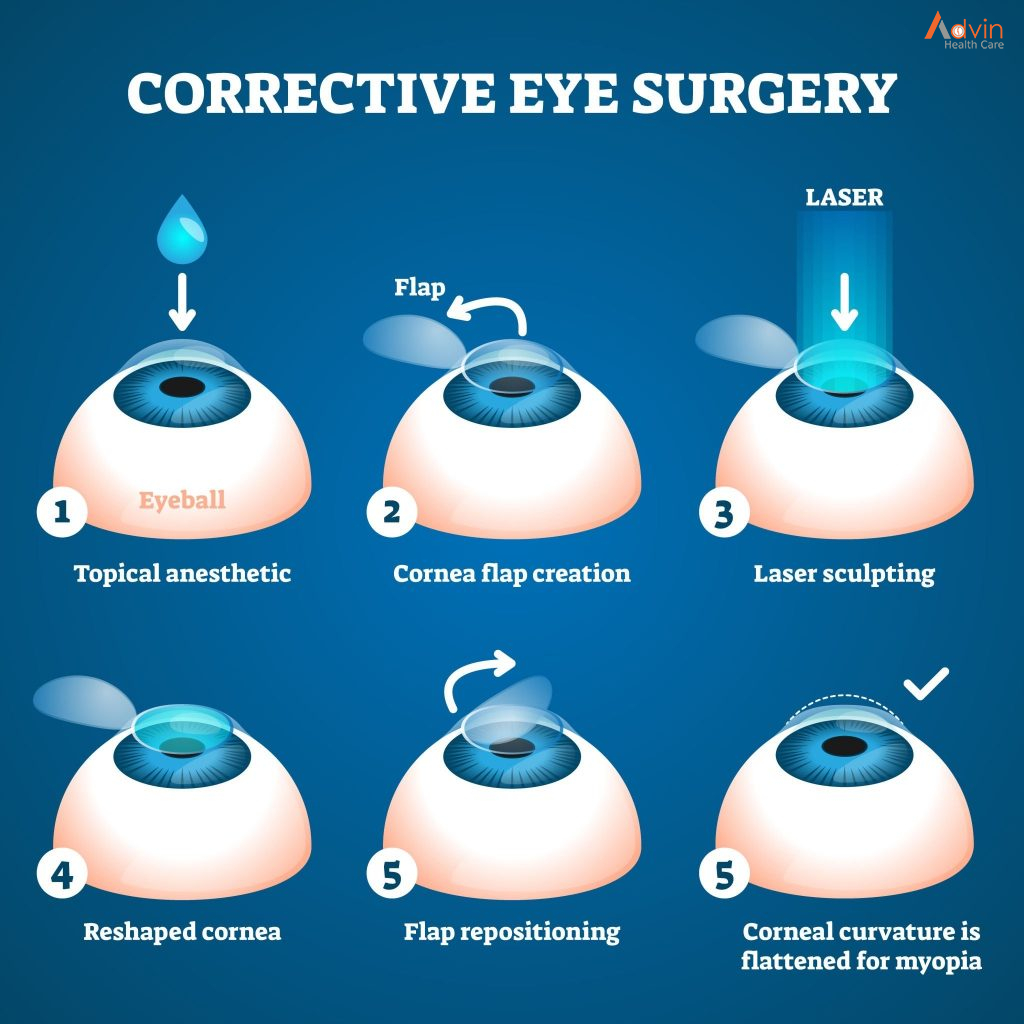

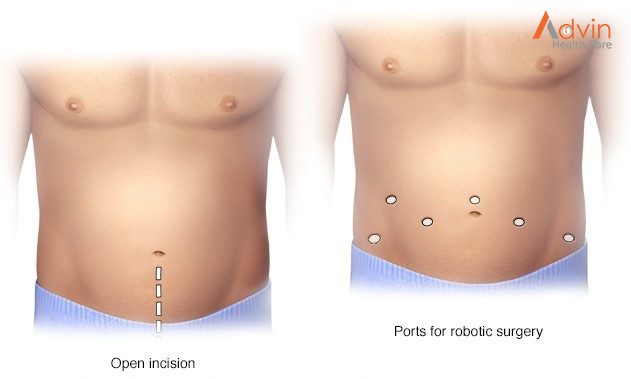

Your retinal detachment surgery will likely involve a scleral buckling and/or vitrectomy procedure. We use the most advanced surgical equipment and techniques available for retinal detachment surgery. A scleral buckling surgery involves positioning a silicone band around your eye beneath your eye muscles to bring in the walls of your eye. This elongates your eye and makes you more near sighted. A vitrectomy surgery involves making 3 holes in the eye and using instruments to remove the jelly-like substance (the vitreous humour) that normally fills the centre of the eye. The removal of the vitreous inside the eye does not cause any permanent harm. The vitreous is replaced by natural fluid produced inside the eye. The retina is then reattached and all retinal tears surrounded by laser. The eye is then filled with an inert gas to keep the retina in position as it heals. The gas bubble will dissipate from your eye within 4-6 weeks. You cannot change elevation (fly on an airplane) or undergo general anaesthesia with nitrous oxide gas while a gas bubble is in your eye. We will place a green bracelet around your wrist indicating this after surgery, do not take off the bracelet until the gas dissipates from your eye. In certain cases, we may use silicone oil instead of gas; your surgeon will review with you if this is appropriate for your surgery.

Retinal reattachment surgery usually takes one-two hours to perform. It is typically performed the under local anaesthesia so that you are awake and comfortable during the procedure and have minimal complications from anaesthesia postoperatively. If you are awake, it is very important for you stay still during surgery.

What are the benefits of Retina surgery?

The clear benefit of retinal detachment surgery is that it prevents you from blindness in that eye. The degree of recovery of vision is dependent upon a multitude of factors. These include the initial cause of retinal detachment, extent of retinal detachment by the time of initial surgery, pre-existing eye conditions, the presence of retinal PVR scarring, whether your retina re–detaches, and the success of initial surgery which is significantly dependent upon the experience and competence of your surgeon.

Advin Instrument For Retina Surgery

- Barrique Wire Speculum

- Schepens Scleral Depressor

- Gass Retinal Detachment Hook

- Castroviejo Calliper

- Colibri Forceps

- Bishop-Harmon Tissue Forceps

- St.Martin Suturing Forceps

- Wills Hospital Utility Forceps

- McPherson Tying Forceps

- McPherson Forceps

- Hartman Mosquito Forceps

- Vitreous Forceps

- Westcott Stitch Scissors

- Vannes Capsulotomy Scissors

- Vitreous Scissors

- Eye Scissors

- Kalt Needle Holder

- Barra. N. Holder Short Model, Micro Jaws, W/O Lock

- Rycroft Air Injection Cannula

- Bishop-Harmon Anterior Chamber Cannula

- McPherson Corneal Forceps

- Graefe Muscle Hook

- Jameson Muscle Hook

- Schepens Forked Orbital Retractor

- Bard-Parker Handle