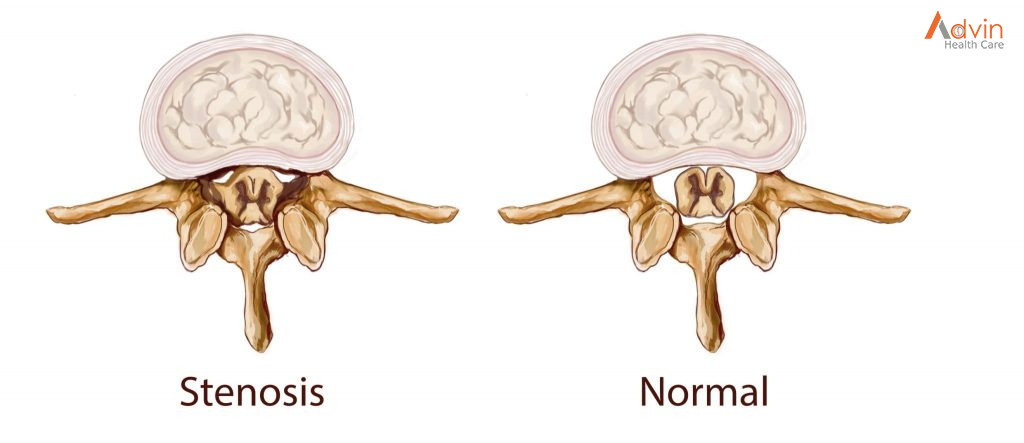

The term “stenosis” is derived from Greek and refers to the process of narrowing that constricts or “chokes” the spinal nerves. The cause of spinal stenosis in the lumbar spine (lower back) is commonly associated with degenerative changes, also known as spondylosis, that occur as a result of aging.

Lumbar spinal stenosis is a common cause of low back and leg pain, or sciatica.

As we age, the normal wear-and-tear effects of aging can lead to narrowing of the spinal canal, which houses the spinal nerves and spinal cord. This condition is called spinal stenosis.

Degenerative changes of the spine are seen in up to 95% of people by the age of 50. Spinal stenosis most often occurs in adults over 60. Pressure on the nerve roots is equally common in men and women.

A small number of people are born with back problems that develop into lumbar spinal stenosis. This is known as congenital spinal stenosis. Typically, this occurs in people who are born with a smaller spinal canal; because there is less space within the canal, degeneration, or arthritis, can affect them sooner. Congenital spinal stenosis occurs most often in men. People usually first notice symptoms between the ages of 30 and 50.

Spinal stenosis occurs when the space around the spinal cord and spinal nerves narrows. This puts pressure on the spinal cord and the spinal nerve roots, and may cause pain, numbness, or weakness in the legs.

Arthritis is the most common cause of spinal stenosis. Arthritis refers to degeneration of any joint in the body.

In the spine, arthritis can result as the disk degenerates and loses water content. In children and young adults, disks have high water content. As we get older, our disks begin to dry out and weaken. This problem causes settling, or collapse, of the disk spaces and loss of disk space height.

As the spine settles, two things occur. First, stress is transferred to the facet joints. Second, the tunnels through which the nerves exit (the foramen) become smaller.

As the facet joints experience increased pressure, they also begin to degenerate and develop arthritis, similar to that occurring in the hip or knee joint. As the facet joint wears down, the body responds by forming bone spurs to stabilize the joint. In addition, the ligaments around the joints that typically connect the bones together, called the ligamenta flava, increase in size. The combination of bone spurs and thickened ligaments crowds the space for the nerves, resulting in stenosis.

Symptoms

- Back pain. People with spinal stenosis may or may not have back pain, depending on the degree of arthritis that has developed.

- Burning pain in buttocks or legs (sciatica). Pressure on spinal nerves can result in pain in the areas that the nerves supply. The pain may be described as an ache or a burning feeling. It typically starts in the area of the buttocks and radiates down the leg. As it progresses, it can result in pain in the foot.

- Numbness or tingling in buttocks or legs. As pressure on the nerve increases, numbness and tingling often accompany the burning pain, although not all patients will have both burning pain, and numbness and tingling.

- Weakness in the legs or foot drop (difficulty lifting the front part of the foot). Once the pressure reaches a critical level, weakness can occur in one or both legs. Some patients will have a foot drop, or the feeling that their foot slaps on the ground while walking.

- Acute cauda equina syndrome. This rare condition is considered a medical emergency that requires prompt treatment. If the compression of the nerves is severe, you can experience numbness in you private area and lose control of your bowel and/or bladder. You may also lose strength in your legs and not be able to walk. If these symptoms occur, you may need emergency surgery.

Who does spinal stenosis affect?

Lumbar spinal stenosis primarily affects those over the age of 50. It has been shown that while nearly 50% of individuals over the age of 60 have lumbar spinal stenosis, not all cases require attention (Fritz et al., 2014). According to current research, there are three principal avenues that one can take to mitigate the degenerative condition that is known as spinal stenosis: physical therapy, epidural cortisone injections and decompressive surgery.

So I have spinal stenosis – what are my next steps?

For patients with spinal stenosis ranging from mild to moderate, physical therapy is the common route chosen. Even with patients suffering from severe spinal stenosis, it is usually recommended that they try some physical therapy before considering surgery. long with physical therapy, treating spinal stenosis through the use of epidural cortisone injections has become quite common. Containing a glucocorticoid and an anaesthetic, the purpose of the injection is to relieve pain by reducing the inflammation caused by the closing of the spinal canal or lateral recesses. The final path that one can choose for treating spinal stenosis is through decompressive surgery. It has been shown that the effectiveness of this method is higher the more severe the case.

How can Physiotherapy help?

Your physiotherapist can help determine which kind of stenosis you have (spinal or lateral). They can provide you with education on your condition (including ways to help), some local manual therapy for your spine and corrective exercises to help improve your core strength and help you to move better.

Which exercises can I try to help?

We’ve listed a few different exercises to help. Some are for general mobility, some are for strength. If you have pain with any of these exercises, then stop and speak with one of our physiotherapists in Markham to help you with symptom relief and to get you moving better.

Knee to Chest stretch

Start in a lying position

Bring one knee to chest and hold for 30 seconds. Repeat for the other side.

Knee to chest exercise

Cat-Camel; Cat-Cow exercise

Start in a four-point position.

Arch your back in one direction then move into the opposite arch. Continue to move from one position to the other. Try 8-12 repetitions. There is no need to hold at the end. There should be NO pain or tingling going down your legs – if there is, discontinue this exercise.

Hip Abduction

Lie on your side. Bend your bottom leg. Keep the top leg straight.

Lift your leg up towards the ceiling. Hold for 1-2 seconds at the top, control the lowering.

These exercises are for guidance only. Discontinue if there is any discomfort with these exercises and contact your physiotherapist for a detailed assessment and alternative exercises.