What is peritoneal dialysis and how does it work?

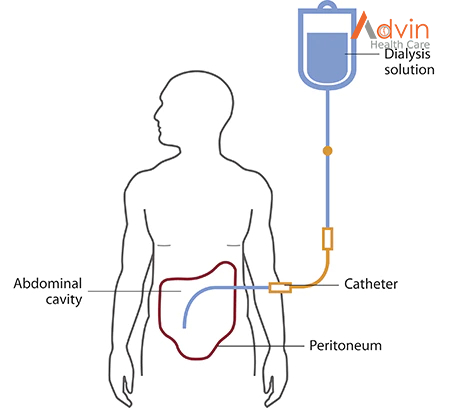

Peritoneal dialysis is a treatment for kidney failure that uses the lining of your abdomen, or belly, to filter your blood inside your body. Health care providers call this lining the peritoneum.

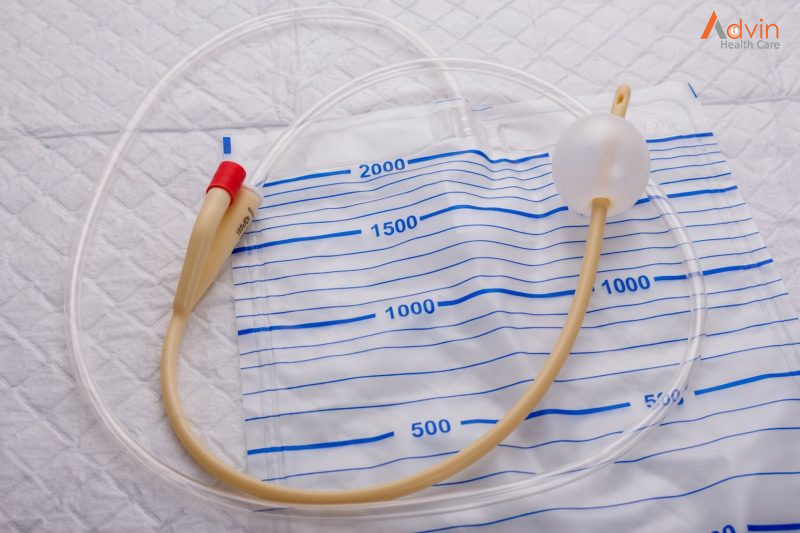

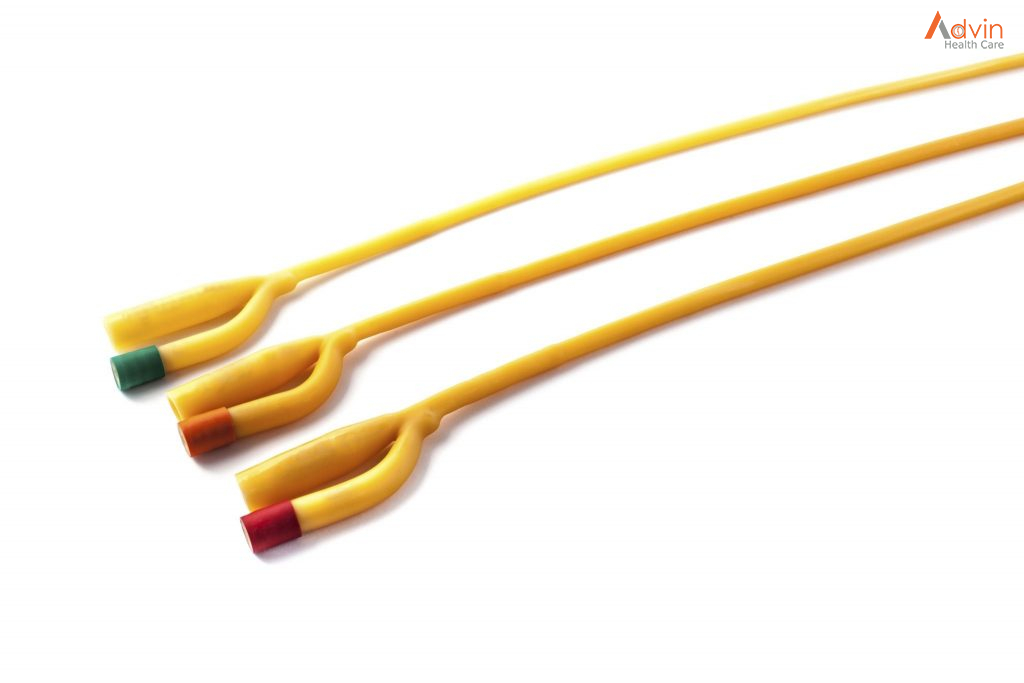

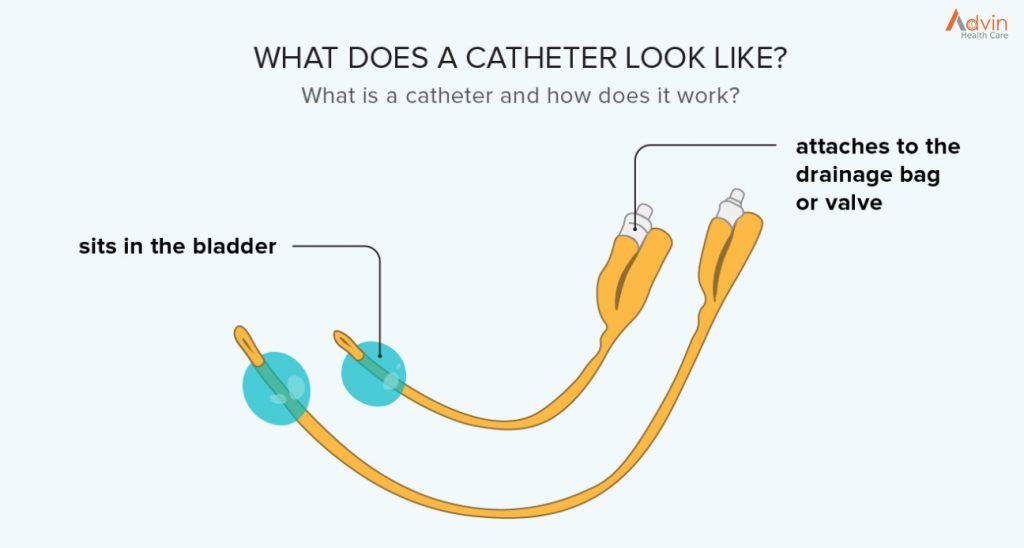

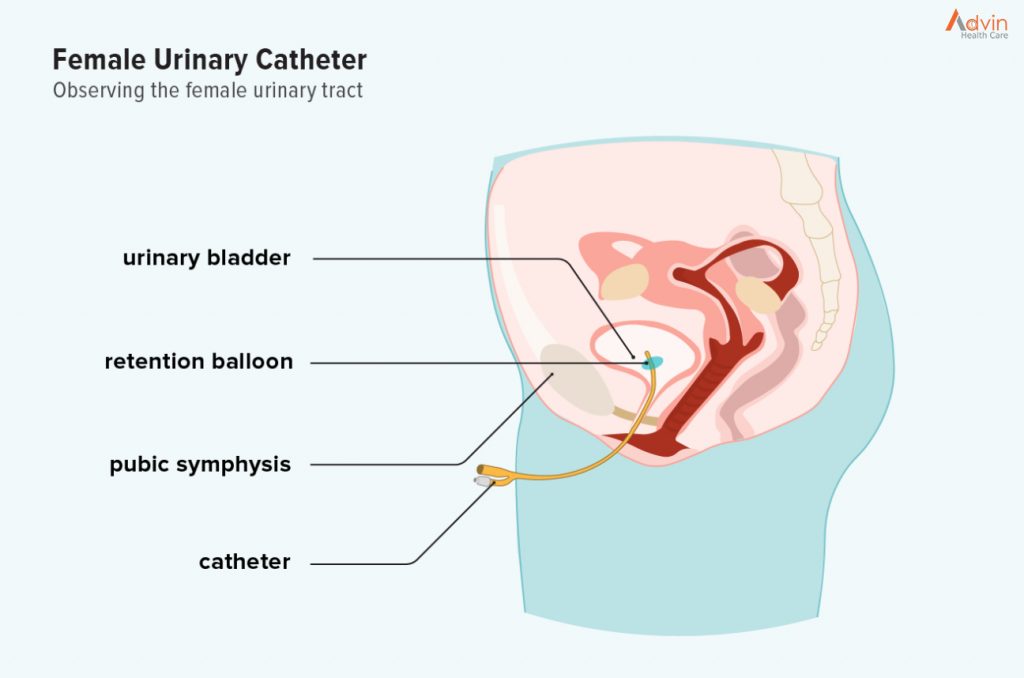

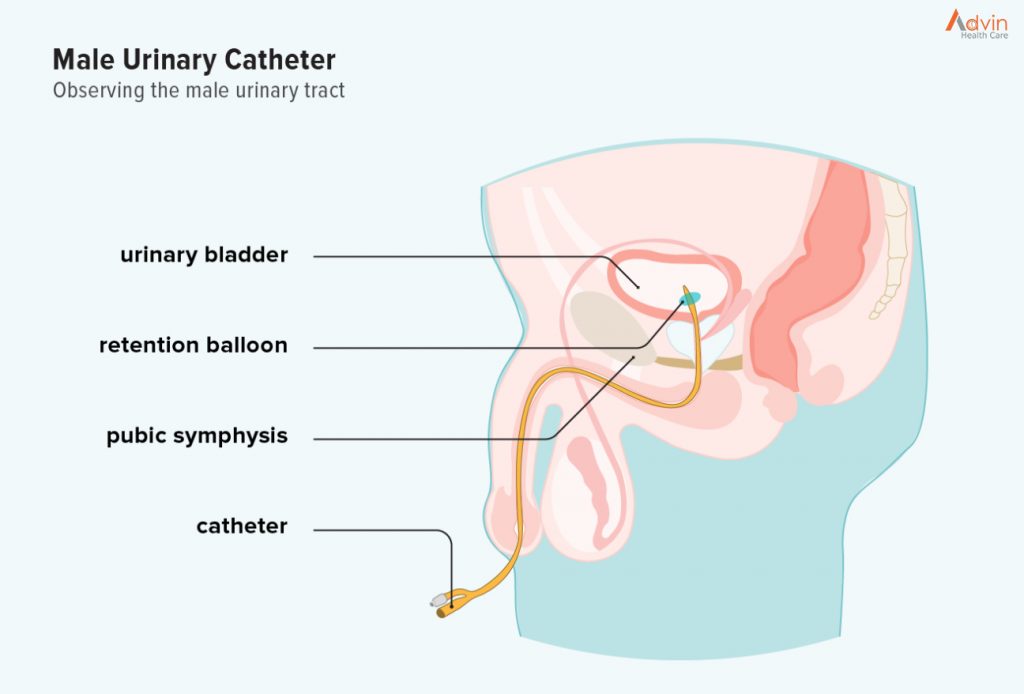

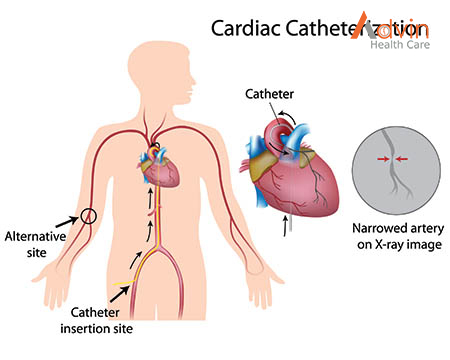

A few weeks before you start peritoneal dialysis, a surgeon places a soft tube, called a catheter, in your belly.

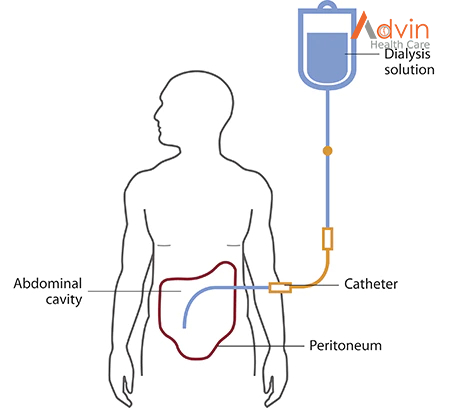

When you start treatment, dialysis solution—water with salt and other additives—flows from a bag through the catheter into your belly. When the bag is empty, you disconnect it and place a cap on your catheter so you can move around and do your normal activities. While the dialysis solution is inside your belly, it absorbs wastes and extra fluid from your body.

After a few hours, the solution and the wastes are drained out of your belly into the empty bag. You can throw away the used solution in a toilet or tub. Then, you start over with a fresh bag of dialysis solution. When the solution is fresh, it absorbs wastes quickly. As time passes, filtering slows. For this reason, you need to repeat the process of emptying the used solution and refilling your belly with fresh solution four to six times every day. This process is called an exchange.

You can do your exchanges during the day, or at night using a machine that pumps the fluid in and out. For the best results, it is important that you perform all of your exchanges as prescribed. Dialysis can help you feel better and live longer, but it is not a cure for kidney failure.

How will I feel when the dialysis solution is inside my belly?

You may feel the same as usual, or you may feel full or bloated. Your belly may enlarge a little. Some people need a larger size of clothing. You shouldn’t feel any pain. Most people look and feel normal despite a belly full of solution.

What are the types of peritoneal dialysis?

You can choose the type of peritoneal dialysis that best fits your life:

- continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD)

- automated peritoneal dialysis

The main differences between the two types of peritoneal dialysis are

- the schedule of exchanges

- one uses a machine and the other is done by hand

If one type of peritoneal dialysis doesn’t suit you, talk with your doctor about trying the other type.

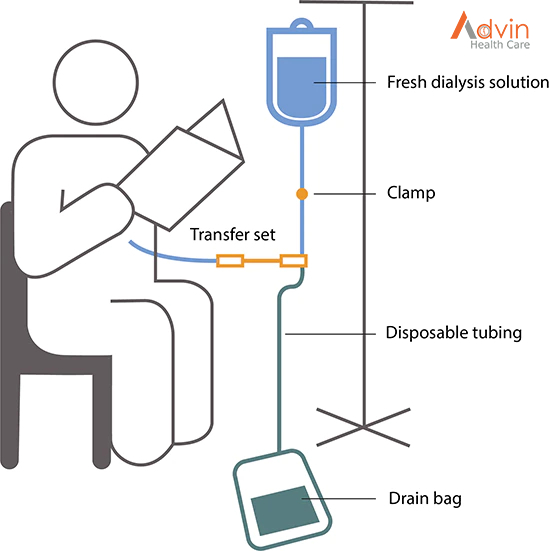

CAPD doesn’t use a machine. You do the exchanges during the day by hand.

You can do exchanges by hand in any clean, well-lit place. Each exchange takes about 30 to 40 minutes. During an exchange, you can read, talk, watch television, or sleep. With CAPD, you keep the solution in your belly for 4 to 6 hours or more. The time that the dialysis solution is in your belly is called the dwell time. Usually, you change the solution at least four times a day and sleep with solution in your belly at night. You do not have to wake up at night to do an exchange.

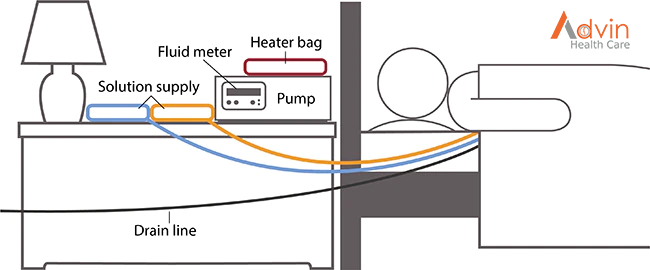

Automated peritoneal dialysis. A machine does the exchanges while you sleep

With automated peritoneal dialysis, a machine called a cycler fills and empties your belly three to five times during the night. In the morning, you begin the day with fresh solution in your belly. You may leave this solution in your belly all day or do one exchange in the middle of the afternoon without the machine. People sometimes call this treatment continuous cycler-assisted peritoneal dialysis or CCPD.

Where can I do peritoneal dialysis?

You can do both CAPD and automated peritoneal dialysis in any clean, private place, including at home, at work, or when travelling.

Before you travel, you can have the manufacturer ship the supplies to where you’re going so they’ll be there when you get there. If you use automated peritoneal dialysis, you’ll have to carry your machine with you or plan to do exchanges by hand while you’re away from home.

How do I prepare for peritoneal dialysis?

Surgery to put in your catheter

Before your first treatment, you will have surgery to place a catheter into your belly. Planning your catheter placement at least 3 weeks before your first exchange can improve treatment success.

Although you can use the catheter for dialysis as soon as it’s in place, the catheter tends to work better when you have 10 to 20 days to heal before starting a full schedule of exchanges.

Your surgeon will make a small cut, often below and a little to the side of your belly button, and then guide the catheter through the slit into your peritoneal cavity. You’ll receive general or local anesthesia NIH external link, and you may need to stay overnight in the hospital. However, most people can go home after the procedure.

You’ll learn to care for the skin around the catheter, called the exit site, as part of your dialysis training.

Dialysis training

After training, most people can perform both types of peritoneal dialysis on their own. You’ll work with a dialysis nurse for 1 to 2 weeks to learn how to do exchanges and avoid infections. Most people bring a family member or friend to training. With a trained friend or family member, you’ll be prepared in case you have a sick day and need help with exchanges.

If you choose automated peritoneal dialysis, you’ll learn how to

- prepare the cycler

- connect the bags of dialysis solution

- place the drain tube

If you choose automated peritoneal dialysis, you also need to learn how to do exchanges by hand in case of a power failure or if you need an exchange during the day in addition to nighttime automated peritoneal dialysis.

How do I perform an exchange?

You’ll need the following supplies:

- transfer set

- dialysis solution

- supplies to keep your exit site clean

If you choose automated peritoneal dialysis you’ll need a cycler.

Your health care team will provide everything you need to begin peritoneal dialysis and help you arrange to have supplies such as dialysis solution and surgical masks delivered to your home, usually once a month. Careful hand washing before and wearing a surgical mask over your nose and mouth while you connect your catheter to the transfer set can help prevent infection.

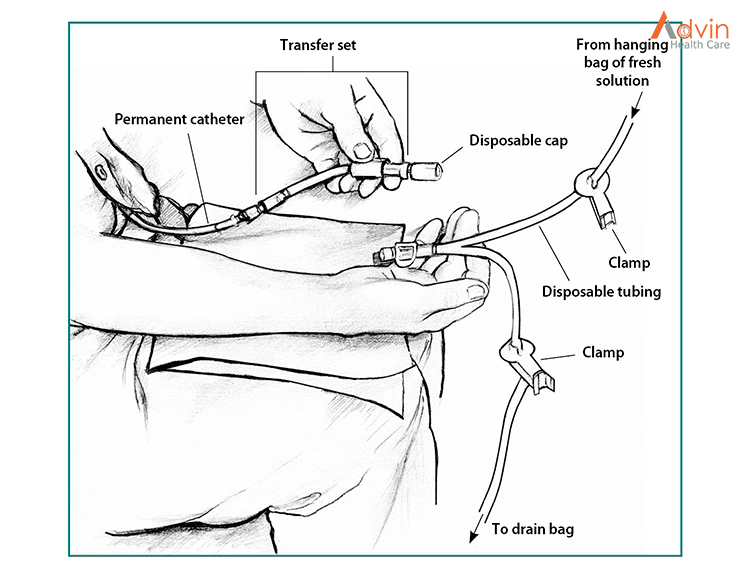

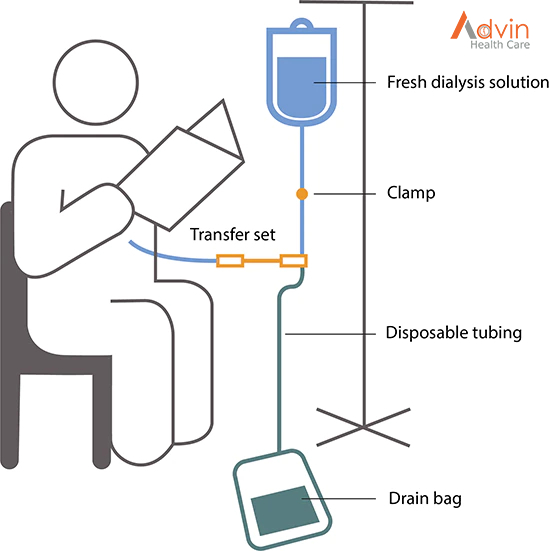

Use a transfer set to connect your catheter to the dialysis solution

A transfer set is tubing that you use to connect your catheter to the bag of dialysis solution. When you first get your catheter, the section of tube that sticks out from your skin will have a secure cap on the end to prevent infection. A connector under the cap will attach to any type of transfer set.

Between exchanges, you can keep your catheter and transfer set hidden inside your clothing. At the beginning of an exchange, you’ll remove the disposable cap from the transfer set and connect the set to a tube that branches like the letter Y. One branch of the Y-tube connects to the drain bag, while the other connects to the bag of fresh dialysis solution.

Use dialysis solution as prescribed

Dialysis solution comes in 1.5-, 2-, 2.5-, or 3-liter bags. Solutions contain a sugar called dextrose or a compound called icodextrin and minerals to pull the wastes and extra fluid from your blood into your belly. Different solutions have different strengths of dextrose or icodextrin. Your doctor will prescribe a formula that fits your needs.

You’ll need a clean space to store your bags of solution and other supplies.

Doing an exchange by hand

- After you wash your hands and put on your surgical mask, drain the used dialysis solution from your belly into the drain bag. Near the end of the drain, you may feel a mild tugging sensation that tells you most of the fluid is gone. Close the transfer set.

- Warm each bag of solution to body temperature before use. You can use an electric blanket, or let the bag sit in a tub of warm water. Most solution bags come in a protective outer wrapper, and you can warm them in a microwave. Don’t microwave a bag of solution after you have removed it from its wrapper.

- Hang the new bag of solution on a pole and connect it to the tubing.

- Remove air from the tubes—allow a small amount of fresh, warm solution to flow directly from the new bag of solution into the drain bag.

- Clamp the tube that goes to the drain bag.

- Open or reconnect the transfer set, and refill your belly with fresh dialysis solution from the hanging bag.

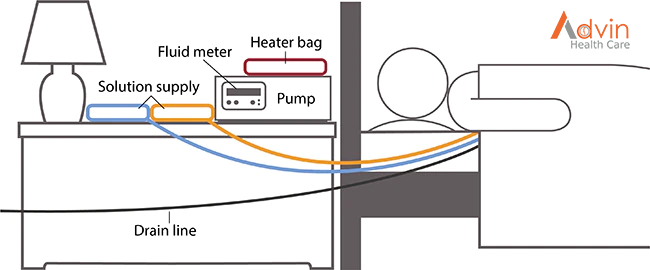

Using a cycler for automated peritoneal dialysis exchanges

In automated peritoneal dialysis, you use a machine called a cycler to fill and drain your belly. You can program the cycler to give you different amounts of dialysis solution at different times.

Each evening, you set up the machine to do three to five exchanges for you. You connect three to five bags of dialysis solution to tubing that goes into the cycler—one bag of solution for each exchange. The machine may have a special tube to connect the bag for the last exchange of the night.

At the times you set, the cycler

- releases a clamp and allows used solution to drain out of your belly into the drain line

- warms the fresh dialysis solution before it enters your body

- releases a clamp to allow body-temperature solution to flow into your belly

A fluid meter in the cycler measures and records how much solution the cycler removes. Some cyclers compare the amount that was put in with the amount that drains out. This feature lets you and your doctor know if the treatment is removing enough fluid from your body.

Some cyclers allow you to use a long drain line that drains directly into your toilet or bathtub. Others have a disposal container.

What changes will I have to make when I start peritoneal dialysis?

Daily routine

Your schedule will change as you work your dialysis exchanges into your routine. If you do CAPD during the day, you have some control over when you do the exchanges. However, you’ll still need to stop your normal activities and take about 30 minutes to perform an exchange. If you do automated peritoneal dialysis, you’ll have to set up your cycler every night.

Physical activity

You may need to limit some physical activities when your belly is full of dialysis solution. You may still be active and play sports, but you should discuss your activities with your health care team.

Make changes to what you eat and drink

If you’re on peritoneal dialysis, you may need to limit

- sodium

- phosphorus

- calories in your eating plan

You may also need to

- watch how much liquid you drink and eat. Your dietitian will help you determine how much liquid you need to consume each day.

- add protein to your diet because peritoneal dialysis removes protein.

- choose foods with the right amount of potassium.

- take supplements made for people with kidney failure.

Eating the right foods can help you feel better while you’re on peritoneal dialysis. Talk with your dialysis center’s dietitian to find a meal plan that works for you.

Medicines

Your doctor may make changes to the medicines you take.

Coping

Adjusting to the effects of kidney failure and the time you spend on dialysis can be hard for both you and your family. You may

- have less energy

- need to give up some activities and duties at work or at home

A counselor or social worker can answer your questions and help you cope NIH external link.

Take care of your exit site, supplies, and catheter to prevent infections

Your health care team will show you how to keep your catheter clean to prevent infections. Here are some general rules:

- Store your supplies in a cool, clean, dry place.

- Inspect each bag of solution for signs of contamination, such as cloudiness, before you use it.

- Find a clean, dry, well-lit space to perform your exchanges.

- Wash your hands every time you need to handle your catheter.

- Clean your skin where your catheter enters your body every day, as instructed by your health care team.

- Wear a surgical mask when performing exchanges.

What are the possible problems from peritoneal dialysis?

Possible problems from peritoneal dialysis include infection, hernia, and weight gain.

Infection

One of the most serious problems related to peritoneal dialysis is infection. You can get an infection of the skin around your catheter exit site or you can develop peritonitis, an infection in the fluid in your belly. Bacteria can enter your body through your catheter as you connect or disconnect it from the bags.

Seek immediate care if you have signs of infection

Signs of an exit site infection include redness, pus, swelling or bulging, and tenderness or pain at the exit site. Health care professionals treat infections at the exit site with antibiotics.

Peritonitis may cause

- pain in the abdomen

- fever

- nausea or vomiting

- redness or pain around your catheter

- unusual color or cloudiness in used dialysis solution

- the catheter cuff to push out from your body—the cuff is the part of the catheter that holds it in place

Health care professionals treat peritonitis with antibiotics. Antibiotics are added to the dialysis solution that you can usually take at home. Quick treatment may prevent additional problems.

Hernia

A hernia is an area of weakness in your abdominal muscle.

Peritoneal dialysis increases your risk for a hernia for a couple of reasons. First, you have an opening in your muscle for your catheter. Second, the weight of the dialysis solution within your belly puts pressure on your muscle. Hernias can occur near your belly button, near the exit site, or in your groin. If you have a swelling or new lump in your groin or belly, talk with your health care professional.

Weight gain from fluid and dextrose

The longer the dialysis solution remains in your belly, the more dextrose your body will absorb from the dialysis solution. This can cause weight gain over time.

Limit weight gain

With CAPD, you might have a problem with the long overnight dwell time. If your body absorbs too much fluid and dextrose overnight, you may be able to use a cycler to exchange your solution once while you sleep. This extra exchange will shorten your dwell time, keep your body from absorbing too much fluid and dextrose, and filter more wastes and extra fluid from your body.

With automated peritoneal dialysis, you may absorb too much solution during the daytime exchange, which has a long dwell time. You may need an extra exchange in the midafternoon to keep your body from absorbing too much solution and to remove more wastes and extra fluid from your body.

Your dietitian can provide helpful guidance to reduce weight gain.