Overview

Cesarean delivery (C-section) is used to deliver a baby through surgical incisions made in the abdomen and uterus.

Planning for a C-section might be necessary if there are certain pregnancy complications. Women who have had a C-section might have another C-section. Often, however, the need for a first-time C-section isn’t clear until after labor starts.

If you’re pregnant, knowing what to expect during and after a C-section can help you prepare.

Cesarean deliveries are generally avoided before 39 weeks of pregnancy so the child has proper time to develop in the womb. Sometimes, however, complications arise and a cesarean delivery must be performed prior to 39 weeks.

Why it’s done

Health care providers might recommend a C-section if:

- Labor isn’t progressing normally. Labor that isn’t progressing (labor dystocia) is one of the most common reasons for a C-section. Issues with labor progression include prolonged first stage (prolonged dilation or opening of the cervix) or prolonged second stage (prolonged time of pushing after complete cervical dilation).

- The baby is in distress. Concern about changes in a baby’s heartbeat might make a C-section the safest option.

- The baby or babies are in an unusual position. A C-section is the safest way to deliver babies whose feet or buttocks enter the birth canal first (breech) or babies whose sides or shoulders come first (transverse).

- You’re carrying more than one baby. A C-section might be needed for women carrying twins, triplets or more. This is especially true if labor starts too early or the babies are not in a head-down position.

- There’s a problem with the placenta. If the placenta covers the opening of the cervix (placenta previa), a C-section is recommended for delivery.

- Prolapsed umbilical cord. A C-section might be recommended if a loop of umbilical cord slips through the cervix in front of the baby.

- There’s a health concern. A C-section might be recommended for women with certain health issues, such as a heart or brain condition.

- There’s a blockage. A large fibroid blocking the birth canal, a pelvic fracture or a baby who has a condition that can cause the head to be unusually large (severe hydrocephalus) might be reasons for a C-section.

- You’ve had a previous C-section or other surgery on the uterus. Although it’s often possible to have a vaginal birth after a C-section, a health care provider might recommend a repeat C-section.

Cesarean Section Procedure

1. Cesarean Section Preparation and Anesthesia

Prior to the surgery, you will receive your anaesthesia, which is usually a regional pain block such as an epidural or spinal block. Regional anaesthesia allows you to feel no pain during the surgery while also remaining awake to witness the birth of your child. In some cases of emergency, general anaesthesia is used, which means you will be asleep.

While your anaesthesia is being administered, the room will be busy as the nurses and doctors prepare the room with instruments and the warmer for the baby. Anaesthesia can take about 20 to 30 minutes to administer. The powerful numbing will happen quickly and effectively.3

Sometimes, your arms will be strapped down in a T-position away from your sides. This is done to prevent you from accidentally interfering with the surgery. You may also have a catheter placed. There will be a drape placed at your abdomen to keep you from seeing directly into the incision. However, you will be able to see the doctors, and most importantly, the baby when they are delivered.

2. Initial Incision

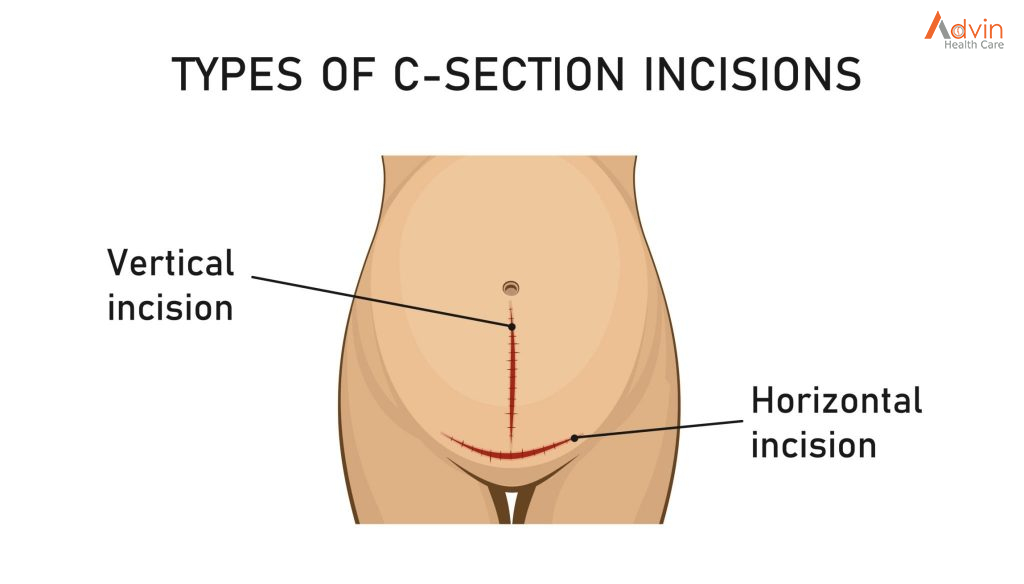

you see that the patient has been draped with sterile drapes and is in the operating room as they make the initial incision into the abdomen. In the vast majority of cases, the incision is horizontal (across the lower abdomen, below the belly button, and just above or below the start of pubic hair).

A vertical incision is usually only used in emergencies or complicated cases where better access to the baby is needed quickly. The drawbacks of a vertical incision are that a VBAC is not possible in later pregnancies due to the risk of uterine rupture and the scar is more visible. On the plus side, this type of incision usually results in less bleeding for the mother.

Also, note that there is no need to shave beforehand. Hospital staff will do this if it is necessary, and it might not be.

3. Follow-Up Incisions

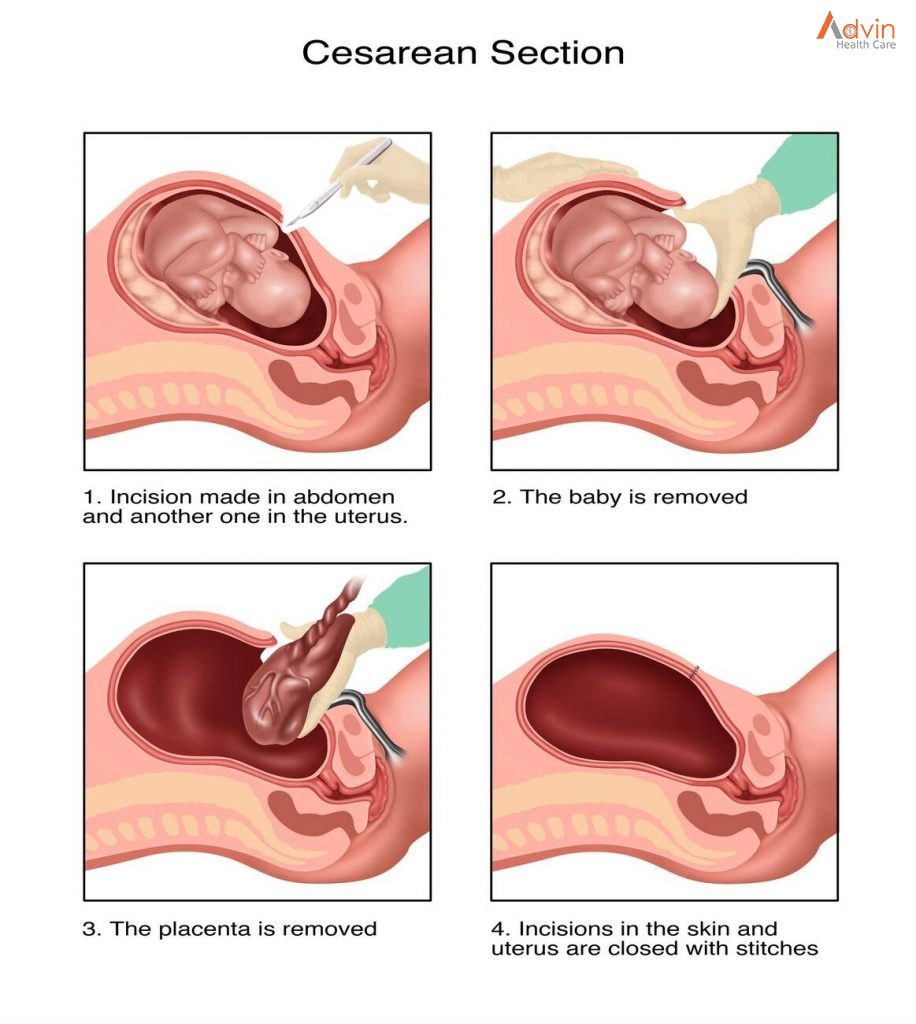

There are multiple layers that your surgeon must go through before reaching the baby.

This includes cutting through the skin, fat, into the abdomen, and uterus. The abdominal muscles won’t be cut but will be separated in order to access the uterus. The bladder and intestines may need to be pushed aside, as well.

The doctor will use a variety of instruments during the procedure as they go through each layer of the body. You may also hear whirring noises from a machine used to cauterize (burn) small blood vessels to prevent excess bleeding. Sometimes, there are strange smells, caused by disinfectants and cauterizing, which is a burning smell.

4. Suctioning of Amniotic Fluids

When the doctor reaches the uterus, you may hear suctioning. After cutting through the uterus, the amniotic fluid will be suctioned away to make a bit more room in the uterus for the doctor’s hands or instruments, such as forceps or a vacuum extractor, which are sometimes used (forceps less often than vacuum extractor but more often neither) to facilitate the extraction of the baby.

5. Delivery of Baby’s Head

Your baby is often engaged in the pelvis, usually, head down, but perhaps rear first or breech. Whatever part has entered the pelvis will be lifted out by the doctors. You may feel pressure, tugging, or pulling at this point. Some people report feeling nauseated during this intense, but brief moment.

Although you may feel pressure, you should not feel pain. The anesthesiologist is usually positioned right by your head in order to monitor your pain and general well-being. Alert them if you feel any pain. They will also often keep you informed about everything that is happening during the procedure and can answer any of your questions.

Once the head is out, your doctor will suction the baby’s nose and mouth for fluids. In a vaginal birth, these are squeezed out by the constriction of labor. In a cesarean birth, the baby needs some extra help getting rid of these fluids. If meconium (the baby’s first bowel movement) is present there may be extra suctioning required.

6. Delivery of Baby’s Shoulders and Body

Once your baby has been well suctioned, the doctor will start to help the rest of the body be born. The surgeon will need to maneuver the baby back and forth to help them emerge. You may feel this, but again, while you may experience sensations of tugging or pulling, this should not be painful.

The doctor will check for umbilical cord entanglement or other complications as the body is born. You may also have the assistant surgeon pressing on the upper part of your abdomen to assist in the birth.

7. Baby Is Born

The moment you’ve been waiting for—your baby’s birth! It’s been about 5 to 10 minutes since your surgery started. Your baby will typically be briefly held over the drape to show you, the umbilical cord will be cut, and then, the baby is taken away by a nursery nurse or neonatologist to a nearby warmer, depending on the setup of the operating room.

If your baby goes to the warmer, it is usually in the same room as the surgery. Here, your baby will be suctioned again to ensure that they have help clearing the amniotic fluid. Your baby may also have some basic care like weighing, measuring, cleaning, and vitamin K.

8. Delivery of the Placenta

The next steps are the delivery of the placenta, followed by the suturing of the uterus and all the layers that were cut during the surgery. Once the placenta has been removed, it will be examined by your doctor.7 Closing up everything that’s been cut through to get to the baby is usually the longest part of the cesarean section, which in total typically takes about 30 to 60 minutes to complete.

During this time you can usually have your baby with you to breastfeed or hold. However, don’t feel pressure to begin breastfeeding immediately, you can start any time in the first hours after your baby is born—a small delay won’t cause any harm. Simply enjoying your baby however works best for you is fine. It may also be possible for your support person to hold the baby close to your face if you are unable to hold your baby.

9. Closing the Incision

After everything is finished surgically, your surgeon will stitch your incision shut. While the uterus is typically sutured (sewn) closed with dissolving stitches, the doctor can choose to close the abdominal incision with either staples or stitches.

There are advantages to both methods—staples are faster (saving around seven minutes), while stitches decrease rates of wound separation and infection and usually yield a finer scar.

The type of wound closing used will depend on physician preference and the specifics of your particular surgery. In a planned procedure, you can discuss the options with your doctor. Once closed, the wound will be covered with a bandage.